A guest blog post by Dr. Andrea Brennan, OTR/L, CLT-LANA, WCC.

Thinking Lymphatically: Part 3 in the series

If you’ve been following the first and second articles in our Think Lymphatically Series, you’re gaining a fresh understanding of chronic edema and lymphedema. In the previous articles, we’ve reexamined Ernest Starling’s famous principle, learned new insights from modern researchers J.R. Levick and C.C. Michel, and come to appreciate the power of the endothelial glycocalyx.

Our purpose for this series is to inspire clinicians to think lymphatically. That’s the theme of this series and one of my personal mottos. In this article, we’ll do a quick review of microvascular fluid exchange and explain the impact of new research on patient care.

We’ll conclude with treatment modalities that can improve patient outcomes. Our goal is to ensure every edema and lymphedema patient always receives the best and most up-to-date treatment possible.

Edema vs. Lymphedema

First, let’s review edema and lymphedema, including important points about the differences between them:

- All edema is lymphatic overload.

- Lymphatic failure is responsible for all forms of edema.

- However, all edema is NOT lymphedema. If someone has edema, it does not mean they also have lymphedema.

- Left unchecked, all edema will eventually become lymphedema.

- Lymphedema occurs when there is too much protein in the interstitium.

- Lymphatic system failure results from either excess fluid on a normal system, a normal amount of fluid on a damaged system, or a combination of both issues.

- Lymphedema does not dissipate on its own. It will continue to progress without adequate treatment.

As medical professionals, if we can facilitate lymphatic drainage so there is no stasis fluid we can work to reduce the consequences of lymphedema. That means if we can nip edema in the bud, and prevent it from worsening, we drastically reduce the chances of lymphedema occurring. This helps preserve a patient’s quality of life.

A Summary of Microvascular Fluid Exchange

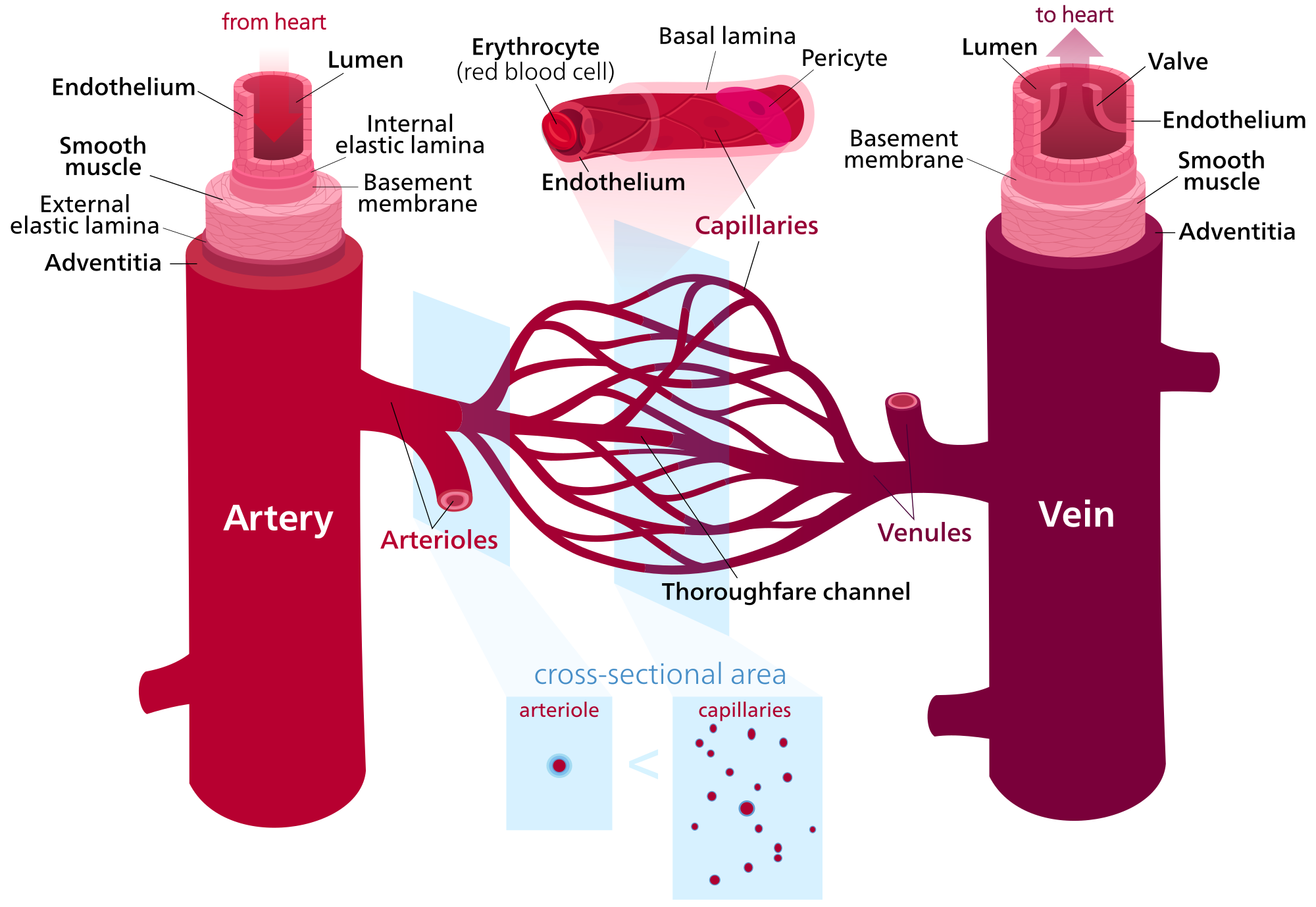

To explain, let’s briefly touch on the basics of microvascular fluid exchange. It has four components: capillaries, tissue channels, proteolytic cells (or macrophages), and initial lymphatics.

Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blood_vessels_(retouched)_-en.svg

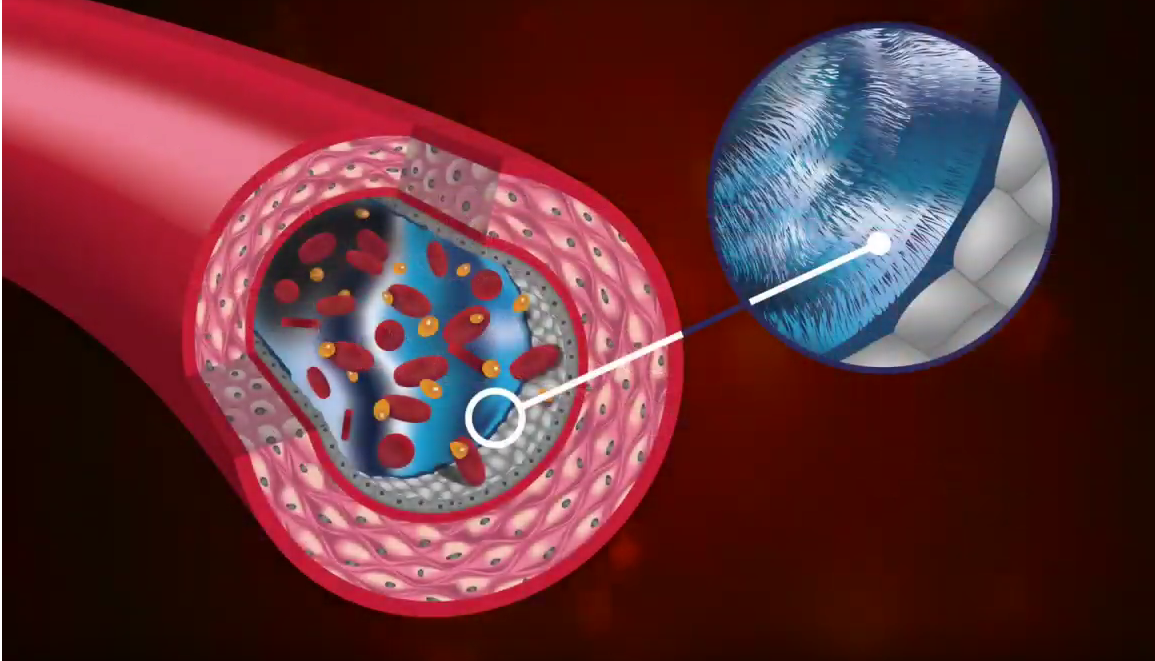

The capillaries have various textures and holes that allow fluid and protein to leave the bloodstream. Between the capillaries and lymphatics is the interstitial fluid, which sits in a channel with macrophages. Macrophages work to break down large particles so they are small enough to enter the lymphatic system.

Whenever this cellular debris can’t be adequately broken down, pressure begins to build. It’s the pressure of osmotic asymmetry, where fluid tries to move from a place of high pressure to lower pressure. Ernest Starling taught us about this pressure and his theory of filtration, but he didn’t have the advantage of modern electron microscopy.

Levick and Michel updated Starling’s work, which identified the importance of the endothelial glycocalyx, a fluid-resistant structure that creates a zone of reduced permeability. This means that essentially 100% of the fluid that leaves the capillary, flows through the interstitium and exits into the lymphatic system. The fluid does not re-enter the capillary at the venous end, as previously conceptualized for the hundred plus years.

Examples of Patient Impact

With the discovery of the glycocalyx and its hydrophobic nature, we’re talking about something revolutionary here. When you step back and think about the real-world meaning for your edema and lymphedema patients, it’s a stunning revelation.

Consider your patients who have health issues like those below.

Edema. Picture someone in the early stages of edema. You can look at them and know that if they don’t receive proper care, and their edema worsens while left untreated, it’s almost certain that they will eventually develop lymphedema.

Diabetes. This is one of many disease states where the glycocalyx begins to wear away. We don’t yet know exactly how or why, but it certainly contributes to swelling. Lymphatic overload may occur. Look for edema comorbid with diabetes.

Obesity. Here’s another opportunity to think lymphatically. Lymphatic dysfunction affects fluid balance, nutritional function, and fat absorption, and it is now considered an active player in the processes behind clinical obesity.

Atherosclerosis/cardiovascular disease. Ernest Starling originally studied cardiac output and its related fluid forces. When the cardiovascular system doesn’t have the right pressure - when it isn’t getting the nourishment it needs - that’s a major problem for the body. Cardiovascular disease is also about thinking lymphatically.

Renal disease. We see swelling with renal disease. It’s another disease state where we see erosion of the glycocalyx and functional impairment of the lymphatic system.

Rheumatoid arthritis. In rheumatoid arthritis, the body’s immune system may cause an attack on its own organs, including tissues in the lymphatic system and the glycocalyx. Damage occurs. Leakage occurs. RA patients are likely to have trouble with fluid and swelling.

Complementary Treatment Modalities

Which treatments have optimal outcomes for patients? This is, of course, the most important question. The best treatment leads to the best quality of life. I recommend:

External compression. The elastic fibers in the body are damaged in lymphedema, with fluid building up in interstitial tissue spaces. External compression can’t solve this problem, but it can provide support and pressure that was lost when the elasticity was lost.

Pneumatic compression in tandem with manual lymph drainage. A doctor only has two hands, but sometimes it takes four hands, or even six hands, to treat a patient. This is where pneumatic compression (a pump) becomes an essential tool.

Pretreatment of fibrotic tissue. Fibrosis reduces the lymphatic capacity to functionally regenerate. It limits the body’s ability to prevent the chronic appearance of lymphedema. So pretreatment of fibrotic tissue leads to better outcomes for lymphedema.

Static compression in conjunction with pneumatic compression. When pneumatic compression is combined with static compression, the benefit is multiplied.

Insurance and Medicare Issues

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the impact of Medicare/Medicaid coverage and insurance coding on the diagnosis and treatment of lymphatic issues. It’s a huge frustration for my patients, and I’m sure for yours too.

There is no single diagnostic code for lymphedema - it’s a tricky mix of venous patients, edema patients, and doctors who may not even consider lymphedema as a diagnosis. I often ask doctors, “How many lymphedema patients do you have?” and they can’t really answer the question.

I encourage you to look beyond the limits of Medicare and insurance. Consider what is truly best for the patient and push for that approach.

The Bottom Line: Think Lymphatically

For my part, I’m working to educate medical professionals, improve treatment options for patients, and help everyone, regardless of their location, around the world learn to think lymphatically. I’m a fan of the following quote from Professor Carlos Mayall, which is included in the International Union of Phlebology consensus document on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Lymphedema:

“The most difficult disease to be treated is not the lymphedema, but the prejudice and ignorance that dwells in the minds of many physicians.”

That’s why I pursued my doctorate. Traveling all over the world to educate medical professionals about the latest in chronic edema and lymphedema is my professional mission.

Thank you for taking the time to educate yourself about these issues. Together, we’ll provide the best possible treatment for your patients.

About The Author

Dr. Andrea Brennan, OTD, OTR/L, CLT-LANA, CI-CS, WCC holds a clinical doctorate in occupational therapy with a specialty in lymphedema practice management. She has been in the field for more than 35 years and has spent the past 20 years specializing in lymphedema diagnosis and treatment.